There is an ongoing discussion in the yoga community about the directionality of the breath – do you begin your inhalation in the chest and then fill the belly or do your fill up the belly first and then expand the chest? This seemingly innocent question can have yoga teachers argue till they are blue in the face. Is there a right answer? Yep, but before we get to it, let’s start at the beginning.

First of all, let’s get our facts straight – we CANNOT breathe into our bellies (if the air does go into your belly, you are in deep trouble). You certainly do and should EXPAND your belly as you breathe in, but not because the air goes there.

To understand the intricate process of respiration, we need to know two important facts.

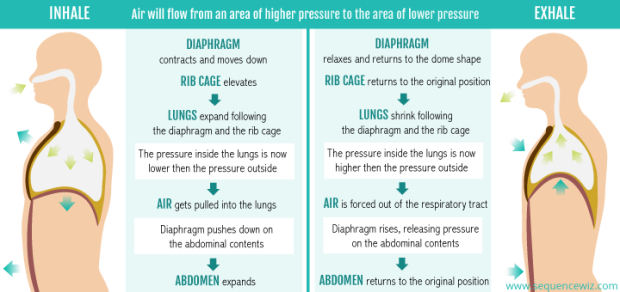

FACT 1: Air will flow from an area of higher pressure to the area of lower pressure

FACT 2: Lungs DO NOT have muscular tissue, which means that you cannot move your lungs at will. Instead the outer surface of the lungs sticks to the inner surface of the ribcage and to the top of the diaphragm; as a result, lungs get pulled following the movement of those structures. So you cannot move your lungs directly, but you COULD intentionally expand the ribcage and, to some degree, affect the movement of the diaphragm (because it is a muscle), which would move your lungs indirectly.

Technically here is what happens when we breathe:

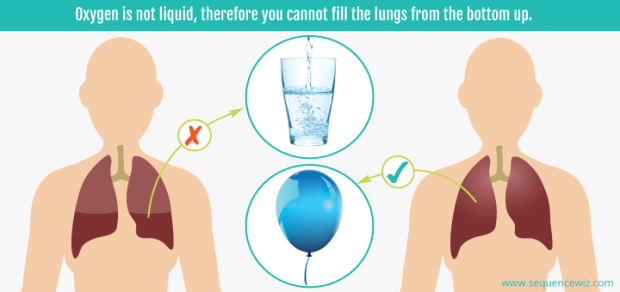

When the air rushes into the lungs, they get filled all at once – you CANNOT fill the bottom of the lungs first and then the top. Oxygen is not liquid, it’s gas; therefore you cannot fill a container (lungs) from the bottom up, like you would with liquid.

The degree of movement of the diaphragm and the ribcage can vary.

- During diaphragmatic or deep breathing we rely mostly on the movement of the diaphragm; it usually occurs at minimal levels of activity.

- During costal, or shallow breathing we rely mostly on the rib cage changing it’s shape and is more common during higher activity levels OR when the contents of the abdominal cavity restricts the movement of the diaphragm (for example, when there is a baby there).

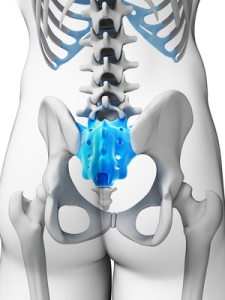

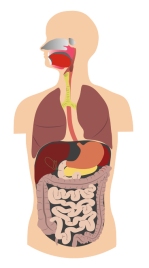

As you can see from this image, your abdominal cavity is packed with stuff – vital organs, digestive tract, etc. When the diaphragm moves down on the inhalation, it pushes down on your abdominal content and it has no other place to go but forward, so your belly pushes forward.

As you can see from this image, your abdominal cavity is packed with stuff – vital organs, digestive tract, etc. When the diaphragm moves down on the inhalation, it pushes down on your abdominal content and it has no other place to go but forward, so your belly pushes forward.

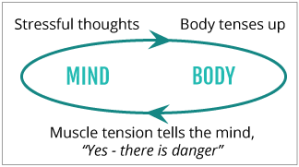

So far we have described the natural pattern of breath: when you breathe in, your chest and your belly both expand AT THE SAME TIME; when you breathe out, both of them return back to the original shape. Now, we CAN use muscular control to change that pattern, consciously or unconsciously. One of the examples of unconscious muscular interference is an unfortunate pattern of “reverse breathing”, when we pull the belly in on the inhale, instead of pushing it out. So if you are keeping your abdomen taut on the inhalation, you are preventing your abdominal contents from moving forward, which means that it will stay where it is and restrict the movement of the diaphragm. So you will end up relying on your rib cage instead; if you do it consistently over time your diaphragm might loose some of it’s elasticity causing shorter and shallower breathing (and who wants that (?!)

When we decide to change the natural pattern consciously, we might CHOOSE to expand the belly first and then expand the chest or we might CHOOSE to expand the chest first and then expand the belly. Both are voluntary actions done for a number of reasons:

Inhale – Expand the belly first then the chest

Inhale – Expand the belly first then the chest

- To emphasize the movement of the diaphragm

- To try to overcome “reverse breathing” pattern

- To produce a grounding effect on the system

Inhale – Expand the chest first then the belly

Inhale – Expand the chest first then the belly

- To lengthen the spine and improve posture

- To gradually deepen the breath

- To have a more uplifting effect on the system

Your exhalation can either be passive or active. With passive exhalation, the muscles that’s been contracting on the Inhale relax and return to their original position. With active exhalation you use your abdominal muscles to compress the abdomen and force the diaphragm upward. If you do your abdominal contraction in a gradual fashion as you exhale, it will help stabilize and support your lower back (read more about the progressive abdominal contraction).

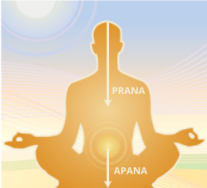

And of course, yogis were very interested in the energetic effects of the breath. Breath is a vehicle for prana, the vital force, that runs in different currents throughout the body. According to Bhagavad Gita, every breath cycle is an opportunity to link prana and apana – two primary currents of the life force.

Apana, which is aligned with the force of gravity, moves downward resulting in elimination of wastes, as well as disease, aging, death and the diminution of consciousness. Prana, which is aligned with the air and space elements is meant to move downward and is responsible for everything we take into the body – food, water, experiences and information. But it can disperse upward through the mind and senses, especially in this age of sensory and information overload. This leads to loss of mind-body coordination and devitalization. Uniting these two primary vayus results in strengthening our energy along with awakening our higher faculties. Yogic practices work to raise apana up to unite with prana and draw prana down to unite with apana, which occurs in the region of the navel – the pranic center in the body.

Apana, which is aligned with the force of gravity, moves downward resulting in elimination of wastes, as well as disease, aging, death and the diminution of consciousness. Prana, which is aligned with the air and space elements is meant to move downward and is responsible for everything we take into the body – food, water, experiences and information. But it can disperse upward through the mind and senses, especially in this age of sensory and information overload. This leads to loss of mind-body coordination and devitalization. Uniting these two primary vayus results in strengthening our energy along with awakening our higher faculties. Yogic practices work to raise apana up to unite with prana and draw prana down to unite with apana, which occurs in the region of the navel – the pranic center in the body.

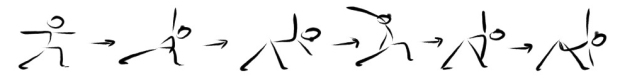

To unite prana and apana, we would focus on the SYMBOLIC downward movement of the breath on the inhalation (nose – throat – expand the chest – expand the belly) and SYMBOLIC upward movement of the breath on the exhalation (progressive abdominal contraction from the pubic bone toward the navel and then deflating the chest).

To unite prana and apana, we would focus on the SYMBOLIC downward movement of the breath on the inhalation (nose – throat – expand the chest – expand the belly) and SYMBOLIC upward movement of the breath on the exhalation (progressive abdominal contraction from the pubic bone toward the navel and then deflating the chest).

So to go back to our original question – which breathing pattern is right – chest to belly or belly to chest – the answer is: It depends! It depends on what you are trying to accomplish.